The reason I fight for democracy and pluralism partly to end once and for all the confluence of political violence and the crisis of injustice in Vietnam, and to end the victimhood as a result of those, partly to secure our country’s position and growth in the prospect of disruptive change.

Chu Tuấn Anh

Democracy and pluralism for ending political violence and injustice

I was born in 1998, just two years before the 21st century, in a rural town, a 2-hour drive from Hanoi’s city centre. Much to the hope that Vietnam would be democratised in the new century, the passage of two decades saw the Communist Regime tighten its grip on power, and there’s no change in sight. I spent my childhood years learning from the regime’s educational system and much of its history textbooks. What has gotten me so opinionated is perhaps my encounters with the victims of injustice, who struggled to scrape by in the capital city’s urban setting, also riddled with urban planning problems and worsening quality of life during my student years.

I did not join the democracy movement with doubts and curiosity, as I did with determination and certainty about what must come along the line after all. Democracy does not automatically bring about greater prosperity, or if it does, by no means for such a short time. It is, however, a tool to resolve the justice crisis left behind by the years under communist rule. The Communist Party should be held accountable for the crisis of political violence wrought on the Vietnamese nation throughout the past century, from the secret campaigns to persecute and murder fellow nationalists and Trotskyists who were also on the broad-church camp of the colonial resistance movement, political cleansing targeted at Landlords and the bourgeoisie, violence suppression of people’s revolts, the Civil War (which ended in 1975), to the crisis of Refugees (or boat people’s crisis after 1975). The 1975 National Unification did not usher in a sense of national reconciliation and healing; it opened the fire for another humanitarian crisis of concentrated education camps and millions of people with bad wounds and acrimony fleeing the country.

The crisis of political violence has prolonged into the next century and broken out into a justice crisis after years of implementing the socialist-oriented economy, in which millions of people fell victim to land grabs and experienced ill treatment, trials, and custody for opposing the State policy that does not recognise private land ownership. And if we try to connect the dots, we learn that the latter crisis broke out because we failed to end the former crisis before the new century came along. This modern-time crisis of injustice has gradually divided our nation into the ordinary people stripped of basic rights and properties, and a small group of communist governors with the communist party, and their cronies. So we’ve seen pauperisation perceived by the majority of powerless people, and the entrenchment of wealth and power enjoyed by a minority of the powerful. But we shall understand that the nature of injustices in Vietnam derives not only from economic inequality or failure to redistribute wealth, but also from political violence and human rights suppression (if narrowly speaking).

As far as I’m concerned, if this time around, this crisis of injustice fails to be put to an end, we might suffer another century-long crisis. I align my views with democracy and pluralism, because democracy allows the recognition of political and civil rights, and the rule of law; the tools to resolve injustices in society; and pluralism is a philosophy that takes into account all the voices of and Vietnamese people of all religions, ethnicities, backgrounds, and social strata in the process of decision making. And in any prospects of democratisation, National Reconciliation must be put to the fore as a philosophy of governance to heal all the divides, and bring all the nation together to the cherishment of a lasting common-sense Vietnamese dream.

Democracy and pluralism for growth and integration in a world of disruptive change

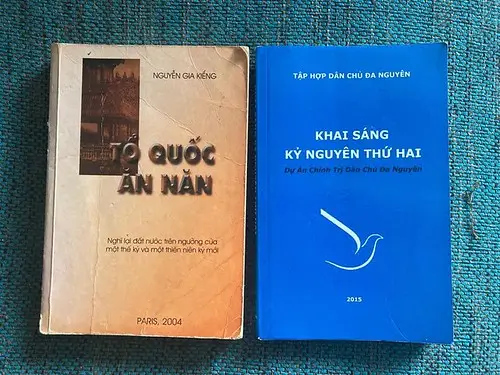

(Download Tổ Quốc Ăn Năn here

Download Khai Sáng Kỷ Nguyên Thứ Hai here)

On the international outlook, I wouldn’t see the polarisation between democracy and dictatorship of the Cold War era. The world, nevertheless, is still fragmented, with democracy failing to pull off a decisive victory as we might have expected when we called it ‘the end of history and the last man‘. The rise of China called into question whether democracy is the only driver of growth. The Western democracies, in the meantime, are turning themselves over their heads, and getting themselves destabilised by enough domestic and international policies’ failure to respond effectively to widespread propaganda by China, Russia, and other illiberal states.

Concerning that, I argued in various articles, China’s model (for much we know as a socialist-oriented economy) might jumpstart a certain degree of growth from its economic infancy, and chalk up new wealth from its extreme poverty owing to economic openness. Such growth is distributed over a few decades, albeit not being guaranteed, as there is a ceiling and limitations to keep it from becoming a high-income nation when middle-income status is already attained. There has been no single evidence to prove that a non-democratic regime would overcome the middle-income trap, and all the countries failing to get rid of this trap will crash into national collapse. In this regard, democratisation is the only way to avoid the prospect of becoming a failed state for Vietnam and any countries that are yet to democratise.

What is more, a system that accrues injustice will inevitably fall, regardless of democracy or dictatorship. Yet, this argument does dwell on the capacity of democracy to review and revitalise itself and is an efficient tool to redress grievances. All in all, democracy is an effective form of governance, and neoliberalism is a deformity by creating multidimensional inequalities within a nation and between nation-states. About time to reclaim the essentials of democracy, which are equality, fairness, universalism of rights and freedoms, and the notion of a universal human in every person.

And when China’s economy is losing out steam, Vietnam has no reason to follow that path of development, as what we need is democracy, which allows the growth to be high-quality, equally distributed, and sustainable; and attached to rights and freedoms, the ingredients of vitality for human development. However, democracy also needs a certain depth of content, a proportionate force, and representatives to fight for it; that’s why I decided to partake in this movement to be part of that force.

The wave of democracy has been put on a brake, not because of democracy failing its terms, the generation of neoliberal politicians has failed to live up to the democratic ideals, for their agenda has been gravitating toward deregulation of the financial market, taxation regimes, and corporatism, and away from democratic rights. That favours the top 1% of big money and their associated 10%, while essentially ignoring 90% of the voters who feel their votes mean little to nothing. This impasse created a perception that democracy does not work, or it does not work for the majority. The backlash of neoliberalism, instead, fuels the rise of populism or the self-appointed speaker of the people who hold democracy in contempt, and in most cases, modern democracy is still strong enough to hold up the physical institutions, waiting for a few years to get the populists out through a free and fair election. The populist vandalism is somewhat beyond repair, with the whitewashing of democratic norms and spirit. Most democratic systems need overhauls, and I’d argue that these overhauls will gather momentum for a refreshed wave of democracy in the years to come. We have to be prepared for that.

The ‘unbribed’ globalisation over the past two decades did not help with building up responsible supply chains, international cooperation based on rule of law and human rights, effective mechanisms and forums to deal with complex trade and international relations issues. It has turned multilateralism into a binary system called ‘Chimerica’, in which China is the manufacturing super engine and America is the world’s largest consumer.

But globalisation has ended as we know it (or at least being re-configured), and a new order of multilateralism is being organised, placing the world in a long period of transition, characterised by the high-speed development of technology, but also chaos and disorder due to the absence of a global leadership following the pullback from America. But a period of transition does not extend borrowed time for authoritarian regimes. That said, it signals the commencement of a refreshed bottle-neck race toward wealth and prosperity, and in the first phase of this race, having strong democratic institutions is a requirement for nation-states to be still up and running and growing through the disruptions. Vietnam lies in the Indo-Pacific Region, the world’s superpower, and where most of the global growth is attained. We stand a possibility of having a fair share of this global growth and secure global integration and a place in the World, if we adopt the right model and approaches.

The reason I fight for democracy and pluralism partly to end once and for all the confluence of political violence and the crisis of injustice in Vietnam, and to end the victimhood as a result of those, partly to secure our country’s position and growth in the prospect of disruptive change.

Why have Vietnamese democrats failed?

We have been severely sanctioned for free speech and freedom of association by the Communist Party; however, we need to make sure our speech, whenever it has a chance to be listened to, should reflect our progressive values and our depth of content proportionate to our national matters of significance; and when our movement could be organised, it should be organised effectively for a wider consensus among dissidents and in society moving forward. We, Vietnamese democrats, are not exempt from ‘why democracy has failed‘, because we failed to gather our little voices into a well-thought-out political project capable of political leadership, and we’ve failed to come together as an effective political organisation to stand for the opposition. We should acknowledge our shortcomings to move forward decisively from this point, as a make-or-break moment has come around this year in 2025. We might not agree about what is to come, but we are all brought to a common awareness that things will not be the same after 2025 for Vietnam and the World. Don’t get me wrong, the Communist Party is being ambushed in new issues after years of kleptocracy and incompetence; they are at their weakest, but we are not in our right form yet either. Our democrats and movement need to be renewed to be proportionate with the stature we need.

For all intents and purposes, I formally endorse the Rally for Democracy and Pluralism (RDP) as my only political affiliation. For it is the loudest and clearest voice of democracy and pluralism, national reconciliation and concord, and non-violent principles. And for the RDP’s ‘Opening a New Era‘ has been the most straightforward political project to democratise Vietnam in a peaceful and reconciliatory spirit, and chart out a new cherished era of human rights and prosperity for all the Vietnamese people, wherever and whoever you are.

Chu Tuấn Anh

(04/08/2025)